No. 2912 (2016.4)

Catalogue Record

Collection

Maker

1882 Ltd

Barnaby Barford

Barnaby Barford

Title

No. 2912

The Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel

Made in

London

Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent

Date

2015

Description

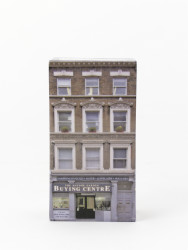

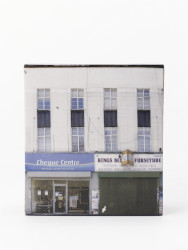

A hollow house-shaped form, slip cast in bone china with a circular hole in the back. The front, sides and pitched roof are decorated with a unique digital decal depicting 49 Broadway Market, London, E8 4PH. This is no.2912, one of 300 individual bone china buildings that made up 'The Tower of Babel', Barnaby Barford's six-metre high representation of contemporary London displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum's Medieval and Renaissance Galleries from 8 September to 1 November 2015.

Materials and techniques

Slip-cast bone china, transfer-printed and glazed.

Dimensions

height: 10cm

width: 5.8cm

depth: 3.8cm

Object number

2016.4

Category

Maker's statement

The Tower of Babel was a huge undertaking, and the artist's most ambitious to date. From conception to reality was 5 years and actual production was 2 and a half years. This is a culmination of all Barnaby’s investigations and experience to date.

“This is London in all its retail glory, our city in the beginning of the 21st century and I’m asking, how does it make you feel?” - Barnaby Barford

The Tower of Babel is a richly-layered work that tells an array of stories about our capital city, our society and economy, and ourselves as consumers. Standing an imposing six metres tall, it is made up of 3000 individual bone china buildings, each between 10 and 13 cm high and each depicting a real London shop. Barford cycled over 1000 miles during the making of The Tower, visiting every postcode in London and photographing well over 6000 shops in the process. These photographs were used to produce the ceramic transfers that have been fired onto the shops, making each shop a unique work of art in its own right.

At The Tower’s base, the shops are derelict, closed-down and boarded-up. Then, as we start to ascend, we find chicken shops, pound shops, and bookies. Climb further and we encounter specialist retailers of all descriptions, chic boutiques and artisan food stores that cater for the aspirational consumer’s every need. Nearing the top, the shops become ever-more exclusive, until finally we reach the pinnacle with London’s fine art galleries and auction houses, where goods are sold at eye-watering prices.

This hierarchy of consumption is echoed in the retail prices of The Tower’s shops, every one of which is for sale. Buy a derelict shop and you might pay £95. Choose a fine art gallery and you could be looking at £6000. In this way, Barford confronts us with the choices we ourselves make as consumers, through financial necessity or materialistic desire. And he reminds us that, through such choices, we both construct our sense of self and shape how others see us.

The Tower of Babel stands as a monument to the pastime of shopping, perhaps the principle leisure pursuit of contemporary British society. Playfully, Barford likens our efforts to find fulfilment through retail to the biblical Tower of Babel’s attempt to reach heaven. His seemingly precarious Tower poses questions about the nature of our society and the fragility of economy, exposing the divide between rich and poor.

Barford’s Tower is also a survey of the streets of early 21st century London. It reminds us not to take for granted how our city actually looks, and how it constantly changes. It reflects, often delightfully, how shop design and graphics impact upon our surroundings and how we feel about certain areas. Perhaps contrary to expectations, it captures an extraordinary diversity in London’s retailers, cataloguing a plethora of independent shops that cater to the needs of their communities. In a direct reversal to the Bible’s Babel – the architects of which were scattered by God and their languages confused – we see shop owners, entrepreneurs and big brands from all over the world, speaking every language under the sun, together, in the city of London, building a tower of commerce.

Alun Graves and Barnaby Barford, 2015.

“This is London in all its retail glory, our city in the beginning of the 21st century and I’m asking, how does it make you feel?” - Barnaby Barford

The Tower of Babel is a richly-layered work that tells an array of stories about our capital city, our society and economy, and ourselves as consumers. Standing an imposing six metres tall, it is made up of 3000 individual bone china buildings, each between 10 and 13 cm high and each depicting a real London shop. Barford cycled over 1000 miles during the making of The Tower, visiting every postcode in London and photographing well over 6000 shops in the process. These photographs were used to produce the ceramic transfers that have been fired onto the shops, making each shop a unique work of art in its own right.

At The Tower’s base, the shops are derelict, closed-down and boarded-up. Then, as we start to ascend, we find chicken shops, pound shops, and bookies. Climb further and we encounter specialist retailers of all descriptions, chic boutiques and artisan food stores that cater for the aspirational consumer’s every need. Nearing the top, the shops become ever-more exclusive, until finally we reach the pinnacle with London’s fine art galleries and auction houses, where goods are sold at eye-watering prices.

This hierarchy of consumption is echoed in the retail prices of The Tower’s shops, every one of which is for sale. Buy a derelict shop and you might pay £95. Choose a fine art gallery and you could be looking at £6000. In this way, Barford confronts us with the choices we ourselves make as consumers, through financial necessity or materialistic desire. And he reminds us that, through such choices, we both construct our sense of self and shape how others see us.

The Tower of Babel stands as a monument to the pastime of shopping, perhaps the principle leisure pursuit of contemporary British society. Playfully, Barford likens our efforts to find fulfilment through retail to the biblical Tower of Babel’s attempt to reach heaven. His seemingly precarious Tower poses questions about the nature of our society and the fragility of economy, exposing the divide between rich and poor.

Barford’s Tower is also a survey of the streets of early 21st century London. It reminds us not to take for granted how our city actually looks, and how it constantly changes. It reflects, often delightfully, how shop design and graphics impact upon our surroundings and how we feel about certain areas. Perhaps contrary to expectations, it captures an extraordinary diversity in London’s retailers, cataloguing a plethora of independent shops that cater to the needs of their communities. In a direct reversal to the Bible’s Babel – the architects of which were scattered by God and their languages confused – we see shop owners, entrepreneurs and big brands from all over the world, speaking every language under the sun, together, in the city of London, building a tower of commerce.

Alun Graves and Barnaby Barford, 2015.